Blaxland’s Journal

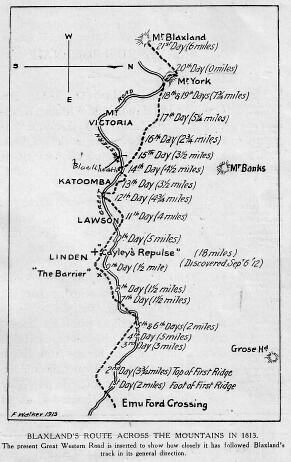

On Tuesday, May 11, 1813, Mr. Gregory Blaxland, Mr. William Went worth, and Lieutenant Lawson, attended by four servants, with five dogs, and four horses laden with provisions, ammunition, and other necessaries, left Mr. Blaxland’s farm at the South Creek 5, for the purpose of endeavouring to effect a passage over the Blue Mountains, between the Western River, and the River Grose. They crossed the Nepean, or Hawkesbury River, at the ford, on to Emu Island 6, at four o’clock p.m., and having proceeded, according to their calculation, two miles in a south-west direction, through forest land and good pasture, encamped at five o’clock at the foot of the first ridge. The distance travelled on this and on the subsequent days was computed by time, the rate being estimated at about two miles per hour. Thus far they were accompanied by two other gentlemen. 7

Blaxland’s route across the mountains in 1813 (sketch map)

On the following morning (May 12), as soon as the heavy dew was off, which was about nine a.m., they proceeded to ascend the ridge at the foot of which they had camped the preceding evening. Here they found a large lagoon of good water, full of very coarse rushes. 8 The high land of Grose Head 9 appeared before them at about seven miles distance, bearing north by east. They proceeded this day about three miles and a quarter, in a direction varying from south-west to west-north-west; but, for a third of the way, due west. The land was covered with scrubby brush-wood, very thick in places, with some trees of ordinary timber, which much incommoded the horses. The greater part of the way they had deep rocky gullies on each side of their track, and the ridge they followed was very crooked and intricate. 10 In the evening they encamped at the head of a deep gully, which they had to descend for water; they found but just enough for the night, contained in a hole in the rock, near which they met with a kangaroo, who had just been killed by an eagle. A small patch of grass supplied the horses for the night.

They found it impossible to travel through the brush before the dew was off, and could not, therefore, proceed at an earlier hour in the morning than nine. After travelling about a mile on the third day, in a west and north-west direction, they arrived at a large tract of forest land, rather hilly, the grass and timber tolerably good, extending, as they imagine, nearly to Grose Head, in the same direction nearly as the river. They computed it at two thousand acres. Here they found a track marked by a European, 11 by cutting the bark of the trees. Several native huts presented themselves at different places. They had not proceeded above two miles, when they found themselves stopped by a brushwood much thicker than they had hitherto met with. This induced them to alter their course, and to endeavour to find another passage to the westward; but every ridge which they explored proved to terminate in a deep rocky precipice; and they had no alternative but to return to the thick brushwood, which appeared to be the main ridge, with the determination to cut a way through for the horses next day. This day some of the horses, while standing, fell several times under their loads. The dogs killed a large kangaroo. The party encamped in the forest tract, with plenty of good grass and water.

On the next morning, leaving two men to take care of the horses and provisions, they proceeded to cut a path through the thick brushwood, on what they considered as the main ridge of the mountain, between the Western River and the River Grose; keeping the heads of the gullies, which were supposed to empty themselves into the Western River on their left hand, and into the River Grose on their right. As they ascended the mountain these gullies became much deeper and more rocky on each side. They now began to mark their track by cutting the bark of the trees on two sides. 12 Having cut their way for about five miles, they returned in the evening to the spot on which they had encamped the night before. The fifth day was spent in prosecuting the same tedious operation; 13 but, as much time was necessarily lost in walking twice over the track cleared the day before, they were unable to cut away more than two miles further. They found no food for the horses the whole way. An emu was heard on the other side of the gully, calling continually in the night.

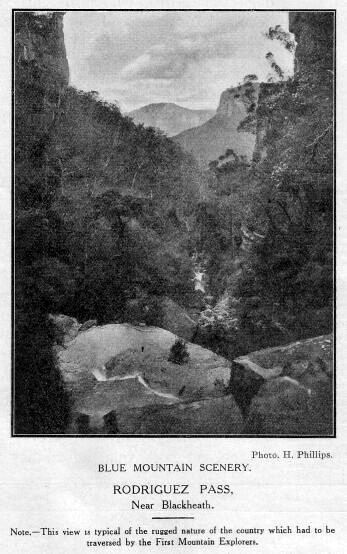

Blue Mountain Scenery — Rodriguez Pass, near Blackheath

On Sunday they rested, and arranged their future plan. They had reason, however, to regret this suspension of their proceedings, as it gave the men leisure to ruminate on their danger; and it was for some time doubtful whether, on the next day, they could be persuaded to venture farther. 14 The dogs this day killed two small kangaroos. They barked and ran off continually during the whole night; and at day-light, a most tremendous howling of native dogs was heard, who appeared to have been watching them during the night.

On Monday, the 17th, having laden the horses with as much grass as could be put on them, in addition to their other burdens, they moved forward along the path which they had cleared and marked, about six miles and a half. The bearing of the route they had been obliged to keep along the ridge, varied exceedingly; it ran sometimes in a north-north-western direction — sometimes south-east, or due south, but generally south-west, or south-south-west. 15 They encamped in the afternoon between two very deep gulleys, on a narrow bridge, Grose Head bearing north-east by north; and Mount Banks north-west by west. They had to fetch water up the side of the precipice, about six hundred feet high, and could get scarcely enough for the party. 16 The horses had none this night; they performed their journey well, not having to stand under their loads.

The following day was spent in cutting a passage through the brushwood, for a mile and a half further. They returned to their camp at five o’clock, very much tired and dispirited. The ridge, which was not more than fifteen or twenty yards over, with deep precipices on each side, was rendered almost impassable by a perpendicular mass of rock, nearly thirty feet high, extending across the whole breadth, with the exception of a small broken rugged track in the centre. By removing a few large stones, they were enabled to pass. 17

On Wednesday, the 19th, the party moved forward along this path; bearing chiefly west, and west-south-east. They now began to ascend the second ridge 18 of the mountains, and from this elevation they obtained for the first time an extensive view of the settlements below. Mount Banks bore north-west; Grose Head, north-east; Prospect Hill, east by south; the Seven Hills, east-north-east; Windsor, northeast by east. At a little distance from the spot at which they began the ascent, they found a pyramidical heap of stones 19, the work, evidently, of some European, one side of which the natives had opened, probably in the expectation of finding some treasure deposited in it. This pile they concluded to be the one erected by Mr. Bass, to mark the end of his journey. 20 That gentleman attempted, some time ago, to pass the mountains, and to penetrate into the interior; but having got thus far, he gave up the undertaking as impracticable; reporting, on his return, that it was impossible to find a passage even for a person on foot. Here, therefore, the party had the satisfaction of believing that they had penetrated as far as any European had been before them.

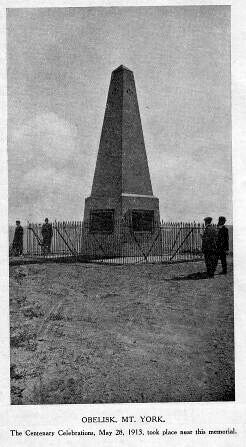

The Obelisk, Mt. York

They encamped this day to refresh their horses, at the head of a swamp covered with a coarse rushy grass, with a small run of good water through the middle of it. 21 In the afternoon, they left their camp to mark and cut a road for the next day.

They proceeded with the horses on the 20th nearly five miles, and encamped at noon at the head of a swamp about three acres in extent, covered with the same coarse rushy grass as the last station, with a stream of water running through it. 22 The horses were obliged to feed on the swamp grass, as nothing better could be found for them. The travellers left the camp as before, in the afternoon, to cut a road for the morrow’s journey. The ridge along which their course lay now became wider and more rocky, but was still covered with brush and small crooked timber, except at the heads of the different streams of water which ran down the side of the mountain, where the land was swampy and clear of trees. The track of scarcely any animal was to be seen, and very few birds. One man was here taken dangerously ill with a cold. Bearing of the route at first, south-westerly; afterwards north-north-west, and west-north-west.

Their progress the next day was nearly four miles, in a direction still varying from north-west-by-north to south-west. They encamped in the middle of the day at the head of a well-watered swamp, about five acres in extent; pursuing, as before, their operations in the afternoon. 23 In the beginning of the night the dogs ran off and barked violently. At the same time something was distinctly heard to run through the brushwood, which they supposed to be one of the horses got loose; but they had reason to believe afterwards that they had been in great danger — that the natives had followed their track, and advanced on them in the night, intending to have speared them by the light of their fire, but that the dogs drove them off. 24

On Saturday, the 22nd instant, they proceeded in the track marked the preceding day rather more than three miles, in a south-westerly direction, when they reached the summit of the third and highest ridge of the mountains southward of Mount Banks. 25 From the bearing of Prospect Hill and Grose Head, they computed this spot to be eighteen miles in a straight line from the River Nepean 26, at the point at which they crossed it. On the top of this ridge they found about two thousand acres of land clear of trees, covered with loose stones and short coarse grass, such as grows on some of the commons in England. Over this heath they proceeded for about a mile and a half, in a south-westerly direction, and encamped by the side of a fine stream of water, with just wood enough on the banks to serve for firewood. From the summit they had a fine view of all the settlements and country eastward, and of a great extent of country to the westward and south-west. But their progress in both the latter directions was stopped by an impassable barrier of rock, which appeared to divide the interior from the coast as with a stone wall, rising perpendicularly out of the side of the mountain. 27

In the afternoon they left their little camp in the charge of three of the men, and made an attempt to descend the precipice by following some of the streams of water, or by getting down at some of the projecting points where the rocks had fallen in; but they were baffled in every instance. In some places the perpendicular height of the rocks above the earth below could not be less than four hundred feet. Could they have accomplished a descent, they hoped to procure mineral specimens which might throw light on the geological character of the country, as the strata appeared to be exposed for many hundred feet, from the top of the rock to the beds of the several rivers beneath. The broken rocky country on the western side of the cow pasture has the appearance of having acquired its present form from an earthquake, or some other dreadful convulsion of nature, at a much later period than the mountains northward, of which Mount Banks forms the southern extremity. The aspect of the country which lay beneath them much disappointed the travellers: it appeared to consist of sand and small scrubby brushwood, intersected with broken rocky mountains, with streams of water running between them to the eastward, towards one point, where they probably form the Western River, and enter the mountains.

They now flattered themselves that they had surmounted half the difficulties of their undertaking, expecting to find a passage down the mountain more to the northward. 28

On the next day they proceeded about three miles and a half; but the trouble occasioned by the horses when they got off the open land induced them to recur to their former plan of devoting the afternoon to marking and clearing a tract for the ensuing day, as the most expeditious method of proceeding, notwithstanding that they had to go twice over the same ground. The bearing of their course this day was, at first, north-east and north, and then changed to north-west and north-north-west. They encamped on the side of a swamp, with a beautiful stream of water running through it.

Their progress on the next day was four miles and a-half, in a direction varying from north-north-west to south-south-west: they encamped, as before, at the head of a swamp. 29 This day, between ten and eleven a.m., they obtained a sight of the country below, when the clouds ascended. 30 As they were marking a road for the morrow, they heard a native chopping wood very near them, who fled at the approach of the dogs.

On Tuesday, the 25th, they could proceed only three miles and a-half in a varying direction, encamping at two o’clock at the side of a swamp. The underwood being very prickly and full of small thorns, annoyed them very much. This day they saw the track of the wombat (an animal which burrows in the ground as a badger, and lives on grass) for the first time. On the 26th they proceeded two miles and three-quarters. The brush still continued to be very thorny. The land to the westward appeared sandy and barren. This day they saw the fires of some natives below; the number they computed at about thirty — men, women, and children. They noticed also more tracks of the wombat. On the 27th they proceeded five miles and a quarter — part of the way over another piece of clear land, without trees 31; they saw more native fires, and about the same number as before, but more in their direct course. From the top of the rocks they saw a large piece of land below, clear of trees, but apparently a poor reedy swamp. They met with some good timber in this day’s route. 32

The bearing of the route for the last three days has been chiefly north and north-west.

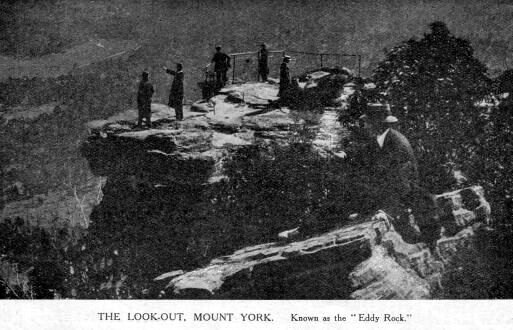

The lookout, Mt. York. Known as the “Eddy Rock”

On the 28th they proceeded about five miles and three-quarters. Not being able to find water, they did not halt till five o’clock, when they took up their station on the edge of the precipice. 33 To their great satisfaction, they discovered that what they had supposed to be sandy barren land below the mountain, was forest land, covered with good grass and with timber of an inferior quality. In the evening they contrived to get their horses down the mountain by cutting a small trench with a hoe, which kept them from slipping, where they again tasted fresh grass for the first time since they left the forest land on the other side of the mountain. They were getting into miserable condition. Water was found about two miles below the foot of the mountain. 34 The second camp of natives moved before them about three miles. In this day’s route little timber was observed fit for building.

On the 29th, having got up the horses and laden them, they began to descend the mountain (Mt. York) 35 at seven o’clock through a pass in the rock, about thirty feet wide, which they had discovered the day before, when the want of water put them on the alert. 36 Part of the descent was so steep that the horses could but just keep their footing without a load, so that, for some way, the party were obliged to carry the packages themselves. A cart road might, however, easily be made by cutting a slanting trench along the side of the mountain, which is here covered with earth. This pass is, according to their computation, about twenty miles north-west, in a straight line from the point at which they ascended the summit of the mountains. 37 They reached the foot at nine o’clock a.m., and proceeded two miles north-north-west, mostly through open meadow land, clear of trees, the grass from two to three feet high. They encamped on the bank of a fine stream of water. 38 The natives, as observed by the smoke of their fires, moved before them as yesterday. The dogs killed a kangaroo, which was very acceptable, as the party had lived on salt meat since they caught the last. The timber seen this day appeared rotten and unfit for building.

Sunday, the 30th, they rested in their encampment. One of the party shot a kangaroo with his rifle, at a great distance across a wide valley. The climate here was found very much colder than that of the mountain or of the settlements on the east side, where no signs of frost had made its appearance when the party set out. During the night the ground was covered with a thick frost, and a leg of the kangaroo was quite frozen. From the dead and brown appearance of the grass it was evident that the weather had been severe for some time past. We were all much surprised at this degree of cold and frost in the latitude of about 34 degrees. The track of the emu was noticed at several places near the camp.

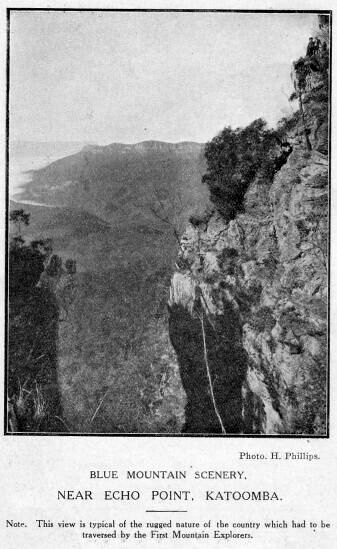

Blue Mountain Scenery — Near Echo point Katoomba

On the Monday they proceeded about six miles, south-west and west, through forest land, remarkably well watered, and several open meadows, clear of trees, and covered with high good grass. They crossed two fine streams of water. 39 Traces of the natives presented themselves in the fires they had left the day before, and in the flowers of the honeysuckle tree scattered around, which had supplied them with food. These flowers, which are shaped like a bottle-brush, are very full of honey. The natives on this side of the mountains appear to have no huts like those on the eastern side, nor do they strip the bark or climb the trees. From the shavings and pieces of sharp stones which they had left, it was evident that they had been busily employed in sharpening their spears.

The party encamped by the side of a fine stream of water, at a short distance from a high hill, in the shape of a sugar-loaf. 40 In the afternoon they ascended its summit, from whence they descried all around, forest or grass land, sufficient in extent in their opinion, to support the stock of the colony for the next thirty years. This was the extreme point of their journey. The distance they had travelled they computed at about fifty-eight miles nearly north-west; that is, fifty miles through the mountain, (the greater part of which they had walked over three times,) and eight miles through the forest land beyond it, reckoning the descent of the mountain to be half-a mile to the foot.

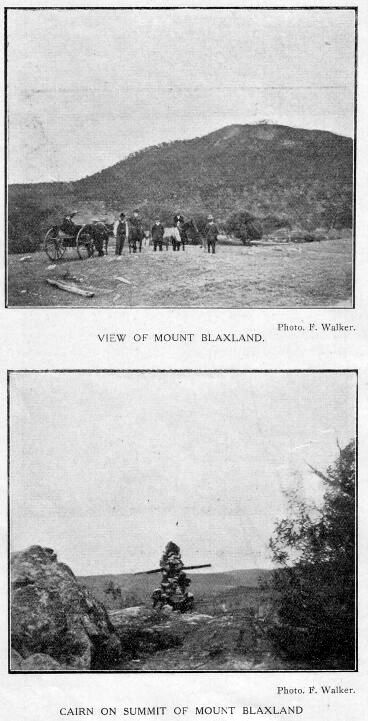

View of Mt. Blaxland and Cairn on summit of Mt. Blaxland

The timber observed this day still appeared unfit for building. The stones at the bottom of the rivers appeared very fine, large-grained, dark coloured granite, of a kind quite different from the mountain rocks, or from any stones which they had ever seen in the colony. 41 Mr. Blaxland and one of the men nearly lost the party to-day by going too far in the pursuit of a kangaroo.

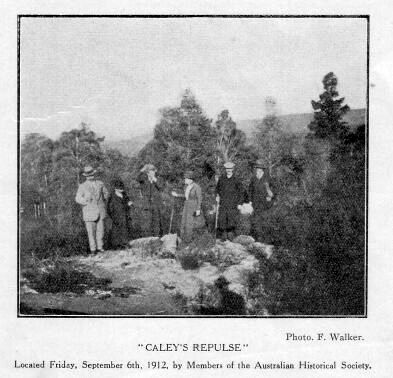

“Caley’s Repulse”

They now conceived 42 that they had sufficiently accomplished the design of their undertaking, having surmounted all the difficulties which had hitherto prevented the interior of the country from being explored, and the colony from being extended. They had partly cleared, or, at least, marked out, a road by which the passage of the mountain might easily be effected. Their provisions were nearly expended, their clothes and shoes were in very bad condition, and the whole party were ill with bowel complaints. These considerations determined them therefore, to return home by the track they came. On Tuesday, the 1st of June, they arrived at the foot of the mountain which they had descended, where they encamped for the night. The following day they began to ascend the mountain at seven o’clock, and reached the summit at ten; they were obliged to carry the packages themselves part of the ascent. They encamped in the evening at one of their old stations. One of the men had left his great coat on the top of the rock, where they reloaded the horses, which was found by the next party who traversed the mountain [Mt. York]. On the 3rd they reached another of their old stations. Here, during the night, they heard a confused noise arising from the eastern settlements below 43, which, after having been so long accustomed to the death-like stillness of the interior, had a very striking effect. On the 4th they arrived at the end of their marked track, and encamped in the forest land where they had cut the grass for their horses. One of the horses fell this day with his load, quite exhausted, and was with difficulty got on, after having his load put on the other horses. The next day, the 5th, was the most unpleasant and fatiguing they had experienced. The track not being marked, they had great difficulty in finding their way back to the river, which they did not reach till four o’clock p.m. 44 They then once more encamped for the night to refresh themselves and the horses. They had no provisions now left except a little flour, but procured some from the settlement on the other side of the river. 45 On Sunday, the 6th of June, they crossed the river after breakfast, and reached their homes, all in good health. The winter had not set in on this side of the mountain, nor had there been any frost.

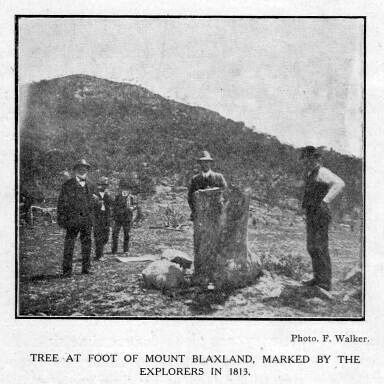

Tree at foot of Mt. Blaxland, marked by the explorers in 1813

5. “Blaxland’s Farm” was situated on the left bank of South Creek, about 3 miles (in 1913) from the present township of St. Marys. The allotment is shown on an early map of the district published in 1808.

6. “Emu Island” does not exist at the present day (1913), but originally it occupied that semi-circular bend of the river about 1 mile north from the railway bridge. Here the stream was shallow enough to permit of an easy crossing. Approaching the river form a northerly direction (their track from the farm would lie in a north-westerly direction), they continued on a diagonal course S.W., and so approached the first range.

7. Names not recorded

8. The “lagoon” mentioned is (in 1913) a body of fresh water lying between Glenbrook station and the preset road.

9. The bearing given of Grose Head (viz. about 7 miles N. by E.), evidently from a position near the lagoon, can be checked at the present day (1913), and a portion of Blaxland’s track thus identified.

10. These are the general characteristics of the country in this locality at the present day (1913).

11. Who was this “European?” Possibly Dawes, Hacking, or Wilson, although it is mere supposition, as there is no definite record to go upon.

12. This was the commencement of the “blazed track”, which method was continued to the termination of their tour at Mount Blaxland. From this point on the return journey great difficulty was experienced in finding their way back to the river.

13. This additional fatigue told severely on the party.

14. This would imply that mutiny was abroad, but evidently the counsels of the leader were listened to, and the trouble was overcome.

15. This is where the difficulty of endeavouring to plot the route of the explorers correctly is encountered. The varied directions as given, imply that some insurmountable obstacles presented themselves all through the journey on this day.

16. This description tallies with the nature of the country between Faulconbridge and Linden. The bearings of Grose Head and Mount Banks (now King George — 1913) would be about correct from this neighbourhood.

17. This ridge may be easily identified as that near Linden station, now (1913) carrying the present road. Its width tallies with that described by Blaxland, and there are deep precipices on either side. The mass of rock still (1913) exists to the east of Linden station. The old Bathurst road will be found on the top. The northern end of the ridge has been cut away to allow of the passage of the present road and railway.

18. This ridge is the one beyond Linden station running N. and S. From a rocky eminence, the bearings given in the text, will be found to agree exactly.

19. Long known (but erroneously called) as “Cayley’s Repulse.” This memorial, or what remains of it (1913) was located on Sept. 6, 1912, by a party of members of the Aust. Historical Society.

20. A mistaken impression, as Bass never reached this portion of the Mountains, judging by his route map and description of the country. The cairn was more probably erected by Hacking or Wilson.

21. This swamp is situated (1913) at the foot of the ridge beyond Linden station, referred to in Note 18.

22. Situated about midway between Hazelbrook and Lawson, probably the source of Hazelbrook Creek.

23. Situated in the neighbourhood of Wentworth Falls.

24. This was the narrowest escape of annihilation the party experienced, being the only time they were really exposed to danger from the attacks of natives.

25. The high ridge beyond Wentworth Falls. As a proof that this is the locality indicated, the spot is due south from Mt. King George (originally named Mt. Banks).

26. A straight line drawn due west from the Nepean would measure exactly 18 miles, showing how remarkably accurate Blaxland was on his computation.

27. They were by now evidently on the edge of some part of the precipice overlooking the Kanimbla Valley, between Leura and Katoomba.

28. The fact that the party resolved to bear more to the north, in their endeavours to find a passage down to the lower lands, is responsible for the accidental arrival on the high tongue of land, now known as Mt. York. It would have been quite probable, otherwise, that they would have attempted the descent of the range in the vicinity of Mt. Victoria pass, where the lay of the country would have presented less difficulty, as regards the descent, than Mt. York. This discovery, however, came afterwards, when a more practicable route was discovered, and the opening of the Victoria Pass in 1832 sealed the fate of the old Bathurst road in its descent of Mt. York.

29. Between Medlow Bath and Blackheath. The swamp is still in existence (1913).

30. By “clouds” Blaxland evidently meant to imply the rising mists from the valley, as they were still coasting along the edge of the precipice.

31. This would answer to the description of the country around Blackheath (in 1913), as they would now be in this locality.

32. This view of the lower lying country would be obtained from a spot in the neighbourhood of Mt. Victoria.

33. The termination of this day’s journey brought them out to the edge of Mt. York. It is quite possible that on observing the low-lying lands beneath him, Blaxland conceived that he had at length reached the termination of the main range, and then decided to push on some distance further, where from one or other of the elevations beyond he would be able to obtain some idea of the country to the westward.

34. “The Lett River”, which was crossed next day. (Named by Evans, and recorded in his journal as the “Riverlett”, meaning the Rivulet. Hence the present name of this stream.)

35. The party evidently returned to the summit of the mountain, where the camp of the evening of May 28 was formed.

36. The first Bathurst road, which passed over Mt. York, was formed along this pass, and traces of the work are still (1912) distinctly visible.

37. Blaxland is somewhat out in his calculation, as a straight line drawn from the summit of the first range, above the Nepean, running N.W., would measure nearer 30 miles — not 20 — as stated.

38. This would bring them to the Lett River at a spot about 1/2 mile south-east of the Hartley Vale road (in 1912)

39. First, the Lett River, lower down its course, and then the Cox River, probably near the junction of the two streams, as the old Bathurst road crossed the latter stream near the junction.

40. Probably Lowther Creek, a tributary of the Cox River. The “sugar-loaf” hill is Mt. Blaxland (named by Evans), and rises above the stream. Two other conical-shaped hills in the near vicinity were also named by Evans, Wentworth and Lawson’s Sugar-loaves. (The write climbed this hill Nov., 1912, and probably stood on the very spot where Blaxland and his party took up their positions, and from where a magnificent prospect, embracing all points of the compass, is obtainable.)

41. This is exactly the appearance the river bed presents today (1913), strewn with large water-worn boulders of dark-coloured granite.

42. On viewing the wide extent of mountainous country to the west, which still had to be passed over, Blaxland in view of the physical condition of the party, and recognising the value of the work already accomplished, decided to return to the settlement, as it was hopeless to proceed further. No doubt his disappointment was keen, when the prospect from the summit of Mt. Blaxland was revealed to him. He possibly anticipated finding a level stretch of country behind the range which shut them in after leaving Mt. York, but was soon undeceived. Under the circumstances Blaxland’s decision was a wise one, and even if he and his party did not complete the entire passage of the Mountains, they, and they alone, are deserving of the honour which will ever be theirs of finding a practical passage across the main portion of this hitherto insurmountable barrier.

43. It is difficult to say what this noise was really occasioned by. It could not have come from the settlements below the Mountains, as surmised by Blaxland, as was more probably some underground disturbance. A curious coincidence is afforded in Bass’s journal, where at one period of his journey he recorded the fact that at a particular spot “he heard the surges roll,” as he expressed it. This was, of course, an utter impossibility, and the origin of the noise was probably the same as that heard by Blaxland.

44. From this point homewards there were no marks on the trees to guide them.

45. In view of the statement concerning the provisions, it appears that the river was crossed twice by at least one member of the party, probably by swimming.